By Sofia Bettiza – BBC World Service

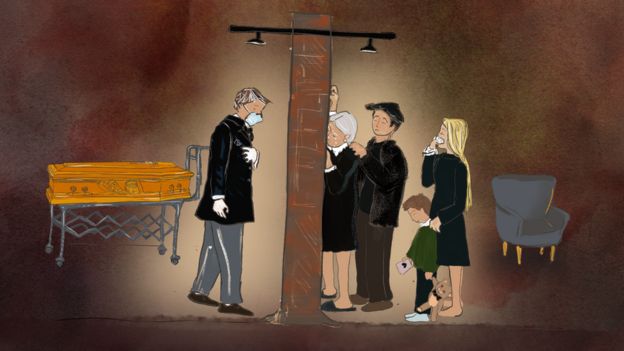

Italy has banned funerals because of the coronavirus crisis. For many, the virus is now robbing families of the chance to say a final goodbye. “This pandemic kills twice,” says Andrea Cerato, who works in a funeral home in Milan. “First, it isolates you from your loved ones right before you die. Then, it doesn’t allow anyone to get closure.” “Families are devastated and find it hard to accept.”

‘They have no choice but to trust us’

In Italy, many victims of Covid-19 are dying in hospital isolation without any family or friends. Visits are banned because the risk of contagion is too high. While health authorities say the virus cannot be transmitted posthumously, it can still survive on clothes for a few hours. This means corpses are being sealed away immediately. “So many families ask us if they can see the body one last time. But it’s forbidden,” says Massimo Mancastroppa, an undertaker in Cremona.

The dead cannot be buried in their finest and favourite clothes. Instead, it is the grim anonymity of a hospital gown. But Massimo is doing what he can. “We put the clothes the family gives us on top of the corpse, as if they were dressed,” he says. “A shirt on top, a skirt below.”

In this unprecedented situation undertakers are suddenly finding themselves acting as replacement families, replacement friends, even replacement priests. People close to those who die from the virus will often be in quarantine themselves. “We take on all responsibility for them,” says Andrea. “We send the loved ones a photo of the coffin that will be used, we then pick up the corpse from the hospital and we bury it or cremate it. They have no choice but to trust us.”

The hardest thing for Andrea is not being able to ease the suffering of the bereaved. Instead of telling families all the things he can do, he is now forced to list everything he is no longer allowed to do. “We can’t dress them up, we can’t brush their hair, we can’t put make up on them. We can’t make them look nice and peaceful. It is very sad.”

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

- MEASURES: What are countries doing?

- HOPE: Five reasons to be positive

- MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

Andrea has been an undertaker for 30 years, just like his father before him. He says small things are usually important for the bereaved. “Caressing their cheek one last time, holding their hand, and seeing them look dignified. Not being able to do that is so traumatic.” In this time of virus, undertakers are often forced to meet grieving families either side of a closed door.

Relatives still try to pass on handwritten notes, family heirlooms, drawings and poems in the hope they will buried alongside their mother or father, brother or sister, son or daughter. But not one of these things will be put in the coffins.

Burying personal items is now illegal. A drastic measure but one designed to stop the spread of the disease. If someone dies at home, undertakers are still allowed inside – but they have to come in wearing full protective gear: glasses, masks, gloves, coats. It is a deeply distressing sight for someone who’s just seen a loved one die. But many undertakers are now in quarantine themselves. Some have had to close their business. A big worry is that those who handle the dead don’t have sufficient masks or gloves.

“We have enough protective gear to keep us going for another week,” says Andrea.

“But when we run out, we will not be able to operate. And we are one of the biggest funeral homes in the country. I can’t even imagine how the rest are coping.” An emergency national law has now banned funeral services in Italy to prevent the spread of the virus. This is unprecedented for a country with such strong Roman Catholic values.

At least once a day, Andrea buries a body and not even one person shows up to say goodbye – because everyone is in quarantine. “One or two people are allowed to be there during burial, but that’s all,” Massimo says. “No-one feels able to say a few words, and so it is just silence.”

Whenever he can, he tries to avoid that. So he drives to a church with the coffin in the car, opens the boot, and asks a priest to perform a blessing there and then. It is often done in seconds. And then the next person awaits.

A country inundated with coffins

Italy’s mortuary industry is overwhelmed and the number of dead keeps rising. Almost 7,000 people have been killed by the virus so far (24 March) – more than any other country in the world. “There’s a queue outside our funeral home in Cremona,” says Andrea. “It’s almost like a supermarket.” Hospital morgues in northern Italy are inundated.

“The chapel at the hospital in Cremona looks more like a warehouse,” says Massimo. Caskets are piling up in churches. In Bergamo, which has the highest number of cases in Italy, the military has had to step in because the city’s cemeteries are now full. One night last week, locals watched in silence as a convoy of army trucks slowly drove more than 70 coffins through the streets. Each one contained the body of a friend or neighbour being taken to a nearby city to be cremated. Few images have been more shocking or poignant since the outbreak began.

Doctors and nurses across the country have been hailed as heroes, saviours in Italy’s darkest hour. But funeral directors have not received recognition for what they too are doing. “Many people see us as merely transporters of souls,” Massimo sighs. He says many Italians look at their work in the way they view that of Charon, the sinister mythological ferryman of the underworld who carries the souls of the newly deceased across a river dividing the world of the living from the world of the dead.

A thankless and unthinking task in the eyes of many. “But I can assure you that all we want is to give dignity to the dead.”

#Andratuttobene – “everything is going to be ok” – is a hashtag that has been trending in Italy since the crisis erupted. It’s accompanied with a rainbow emoji. But at the moment there is no sunshine in sight. And although all pray for it, no-one knows exactly when everything will indeed be ok once again.

*Illustrations by Jilla Dastmalchi